Editor’s Note: Semil Shah works on product for Swell, is a TechCrunch columnist, and an investor – as a disclaimer for this post, he is an advisor to one of the companies mentioned here, Refresh. He blogs at Haywire, and you can follow him on Twitter at @semil.

I may sound like a broken record when I consistently reference this phrase in my weekly column: “mobile is the only under-hyped thing in tech.” Yet, it is hard to argue with, and if we agree to agree, then within a mobile context, almost everything we can do with our phones and apps is under-hyped, as well. Take mobile push notifications, for example. As entrepreneur Ariel Seidman writes, “it’s hard to over-hype the power of mobile push notifications. For the first time in human history, you can tap almost two billion people on the shoulder.”

Push notifications aren’t an entirely new phenomenon, but as mobile handset growth continues to accelerate (along with faster handset releases), push alerts only grow in importance as a channel for applications to communicate with and re-engage users. In theory, push notifications seem elegant, a way to prompt a mobile user at the right place, at the right time, regarding the right piece of information. In practice, however, Apple’s notification channel was flooded by marketing techniques almost out of the gate, taking the great promise of push and watering it down as application developers ruthlessly ask users for the permission to send alerts, and then often abuse that permission. The result? Many mobile users doggy-paddle aimlessly through an ocean of push notifications or some learn about OS-level settings and disable them selectively (or altogether).

It doesn’t have to be like this. I don’t have aggregate data on the ratio between total push notifications sent versus those which are opened, or any specific application-level data, but what I can share — from working in and writing about mobile — is there are some apps which leverage the data on the phone and from their services to send great, timely, contextual, personalized, relevant push notifications, and from these providers, they could be wider lessons we can all learn from. Briefly, here’s what I’ve noticed works for me:

Push notification from red-colored app icons tend to be apps which send me notifications and run in the background, but I rarely open the app itself. The examples which immediately come to mind is the “Breaking News” app, which sends about 4-7 alerts per week. This app has earned my trust to sit on my phone and work in the background, and it doesn’t interrupt me often, so I keep it around. For banking, Bank Of America sends a weekly balance update via push, and then whenever money is credited or debited from my account. Seems appropriate to me, so I keep it around.

Most blue-colored app icons are around messaging and therefore are opened often so I can close that communication loop. The usual suspects are here, like TweetBot, Facebook Messenger, MessageMe, and Mailbox, though I recently decided to disable email push notifications because of the constant buzzing and battery drain. I open the phone to look at email enough already. That said, there is an obvious desire by the user to see a personalized message (like email) and then open the push alert.

Green is an interesting color for push, I recently discovered. The most important green push alert originates from SMS, of course, and since those are the most personalized messages one can receive on their phones, we all pay attention to them. Recently, for the first time, I was tricked into thinking I received another SMS push notification in bright green, only to find it was sent by the crafty folks at one of my new favorite services (Munchery), and perhaps because I like Munchery and pay attention to them in general, the fact that their push icons are green captured my attention before I even realized what happened.

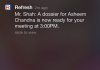

Of course, the color of an app icon and its corresponding push notification are just a surface-level observation, something I noticed personally as my eyes glance at my phone but aren’t fixated on the device. Here are some other examples of push notifications I’ve found to be timely, relevant, contextual, and only sent when appropriate: (1) Refresh sends me a highly-personalized push notification right before any meeting, but goes behind calendar-level data to show me more information about the person I’m going to meet. As a result, I open it nearly every time (see picture above). (2) SnapChat push notifications are opened because there’s timeliness built into the company’s brand, and I know the communication is relevant right now (and will likely also expire when I open it); (3) Lift alerts are tied to explicit daily habits I’ve selected I want to complete, so it perfectly ties together the daily habitual use of smartphones with the things I should be doing anyway; and (4) Circa, a mobile news service, sends me news alerts like the “Breaking News” app, with the added bonus that I can subscribe to a specific story and then be alerted around that, if I opt-in. (There are many other great examples of push done well, but I can’t list them all here.)

The lesson in these apps and others who do not abuse the push notification channel is that the best alerts tend to be personalized, contextual, timely, and relevant — and some don’t require that I go back into the app. It’s this tactic of re-engagement where the trouble starts. Even Facebook mobile ads strategy, which is currently profiting handsomely by arbitraging the difficulty of app discovery among users and the thirst (and willingness to pay) of app developers, recently announced a new ad product targeted at re-engagement, to push users to open and interact with apps which are already on their phones. (A new startup URX is also in this space, where not only is discovery a problem, but engagement is, too.)

Seidman continues: “the basic problem with push notifications is they are used an email replacement. I can see marketers and growth hackers getting all hot n’ heavy realizing that they can now send the weekly “people you should follow” email that nobody reads as a push notification to your mobile device.” And, that’s what usually happens, and why mobile users, over time, begin to intuitively disregard worthless push alerts, either learning to disable the functionality in settings or even deleting the app altogether in frustration. It’s early days in mobile, but I believe the tacky growth-hacky tactics which persist on the web and through email won’t work as well on mobile because push notifications are even more of an interruption and limited to 140 or less characters. This puts app developers in a bind: If an app desperately needs re-engagement, there’s a perverse incentive to flood the notification channel, but if those alerts (and the app itself) aren’t truly relevant to the mobile user, well, the clock starts ticking before either the company doesn’t exist or the user shortcuts it all and deletes the app from the phone altogether.

Read more : The Precise Art Of Mobile Push Notifications

0 Responses

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.